What Do “F-U-N Funerals” and “Death Cafes” Teach Us about Mourning?

- Chris and Elizabeth McKinney

- Aug 6, 2024

- 3 min read

Jesus tells us, “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted” but we’re not so sure. Instead we’ve embraced a counterfeit beatitude: Blessed are those who numb out, for they will be comfortable.

Us westerners don’t do sad well. Maybe that’s why these days, more and more people are wanting “happy funerals.” American author, Erika Dilman, attempts to put the “F-U-N back in Funeral” in her book The Party of Your Life. She helps readers plan their guest list, create a cocktail menu, design a funeral soundtrack, and prepare goody bags. Some feel these celebrations bring a catharsis to their grief and allow attendees to laugh and focus on the positive memories and legacy that their loved one left behind.

Meanwhile, others are attempting to provide outlets for us to express our melancholy feelings. In 2017, a woman named Sue in London felt people didn’t know how to talk about their grief and started something called The Death Cafe. This was meant to be a safe space for people to gather, talk about death and find community with a side of cake. These Death Cafes have struck a chord and have quickly spread across Europe, North America, and into 66 countries. Linda Stuart, grief educator, says: “You may want a party. But you may need a funeral.”

Today, in countries like China and India, where it can be socially unacceptable to weep in public (for men in particular), some go so far as to hire professional mourners. There is a rich history of these paid actors known as moirologists, bringing theatrical demonstrations of chest-beating, loud-crying and tearing of their clothes and hair. Recently, they’re more likely to be paid to cry quietly, as cultural norms are shifting.

Whether we know it or not, all of us have our own grief procedures. While grief is the internal experience of loss, mourning is its outward expression. Grief is what we feel and think; mourning is what we do. It includes the public rituals (funeral and burial procedures) and behaviors (wearing black) that declare this is not the way things were supposed to be. Mourning is our response to grief; it’s how we show that we’re shocked, angry, and sad. The problem is, in the twenty-first-century West, we’re often not very good at it.

Opening up our Bibles—particularly in the Old Testament— we discover a formal approach to mourning that facilitates the expression of one’s sorrow. Though these Jewish customs might initially strike us as strange, God’s people engaged in patterns of mourning which allowed for personal and corporate lament in beautifully structured ways. For example, when a loved one died, life went on hold, and time was set aside for mourning. This began with the initial days of intense bereavement which came to be called “sitting shiva.” Shiva is the Hebrew word for seven, and refers to the seven days following the burial which were designated for weeping (Gen. 23:2) and lamentation (2 Sam. 1:17). This was followed by further time for expressions of grief, lasting thirty days out from the burial. Setting aside time to mourn was one way to give permission to the bereaved that it was okay to not be okay.

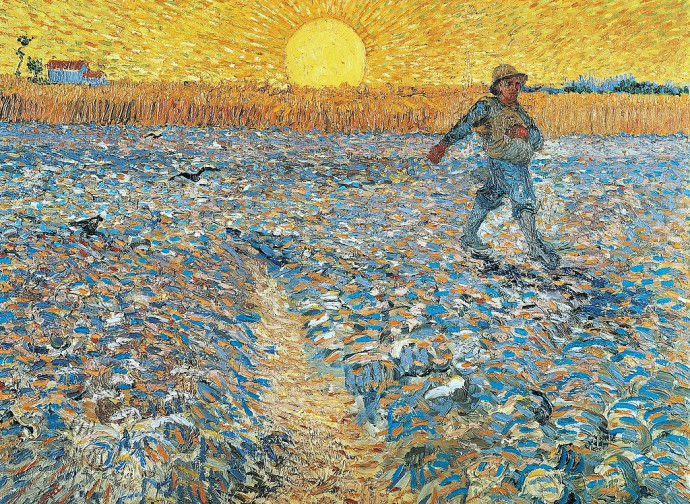

In ancient Near Eastern culture, mourning was dramatic. Today, if we’re looking for healthy ways to express what’s inside, our friends may suggest activities such as journaling or painting. While these are incredibly helpful exercises, they’re also very . . . quiet. Prophets like Ezekiel and Joel however, emphasized weeping, wailing, and groaning in anguish (Ezek. 27:31; Joel 1:5) because grief is sometimes loud.

Read full article at Gospel Centered Discipleship.